Saint Sophrony was born in Moscow in 1896. He arrived at the Russian monastery of Saint Panteleimon on Mount Athos in 1925 and became well-acquainted with Saint Silouan who prior to his death in 1938 entrusted to him his collection of notes. In 1947, Saint Sophrony went to France to prepare a publication of Saint Silouan’s writings. While doing so he became gravely ill and after being hospitalized moved into a nursing home to recuperate. Lacking Office books, he began to pray the Jesus Prayer with other residents as their Office, as well as celebrating the Divine Liturgy. People began coming to pray with the residents and to visit Saint Sophrony. As time went on, these guests repeatedly requested Saint Sophrony to found a monastery. In 1958 he agreed to do so and in 1959 he founded what would become the Stavropegic Monastery of St. John the Baptist at Tolleshunt Knights in Essex, England. It is an Eastern Orthodox monastery of monks and nuns under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople that prays the Jesus Prayer approximately four hours each day for its choral prayer.

During the last four years of his life, Saint Sophrony addressed the community every Monday morning. In 1991 he appointed Father (now Archimandrite) Zacharias Zacharou, the author of this book, to be his assistant and successor. Archimandrite Sophrony died in 1993 at the age of 97. Thus, this book contains a selection of the weekly conferences that Archimandrite Zacharias has given to the community since that time. He is the Spiritual Father or Elder of the community, while Archimandrite Peter Vryzas is the Hegumen (superior).

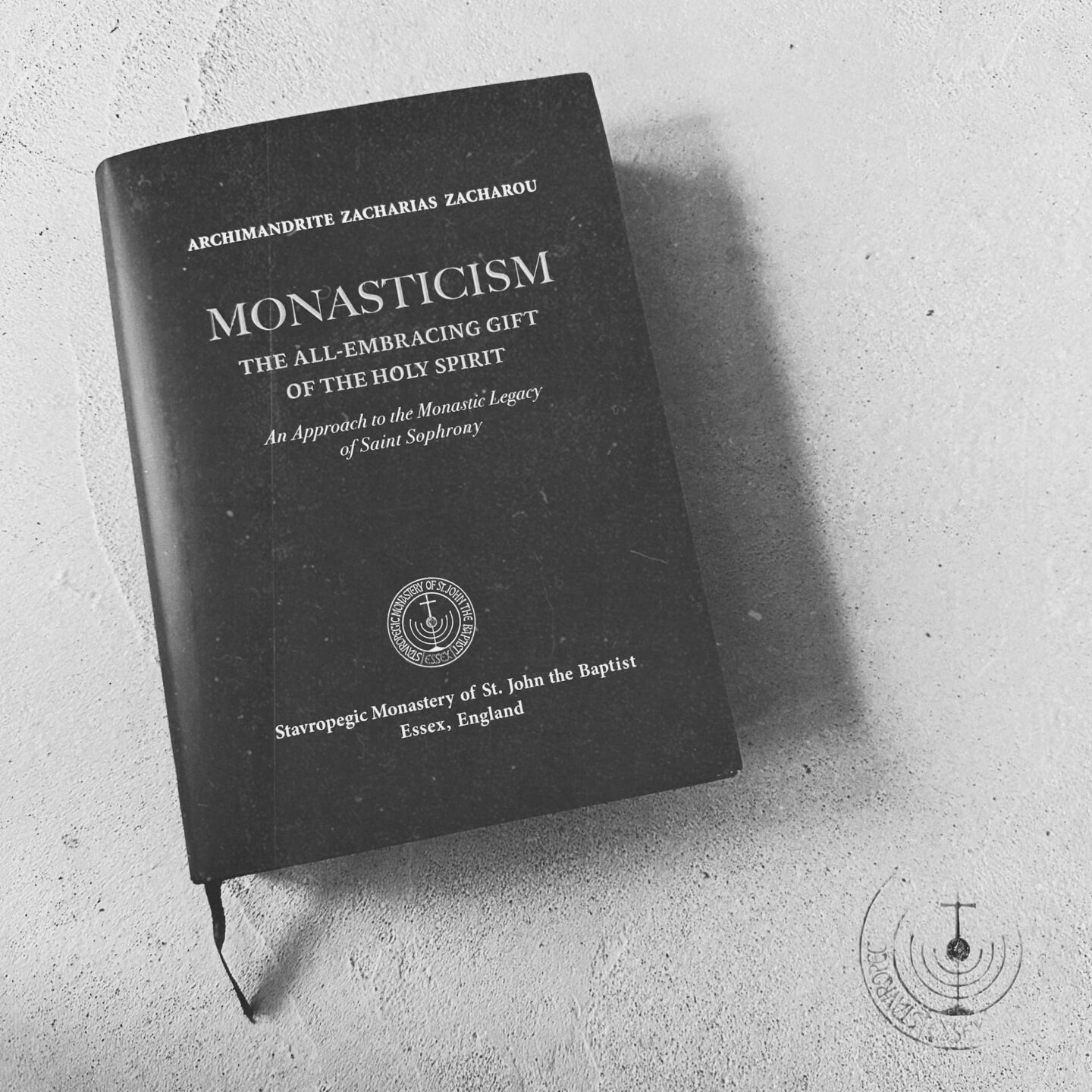

Monasticism: The All-Embracing Gift is divided into three parts. The first section on dimensions of the Gospel in monasticism contains a foundational conference on St. Sophrony’s inverted pyramid of humility, as well as a conference on charismatic theocracy, emphasizing that monasticism is an institution governed by God, “founded upon the two absolute principles of the Name of the Lord and His word”1Archimandrite Zacharias, Monasticism, p. 51.. The second and longest part of the book contains twelve conferences on aspects of the monastic charism including thirst for God, the Name of Jesus, repentance, gratitude, prophetic dimensions of monasticism, the word of God, the elder/disciple relationship, Christlike vulnerability, and affliction. The third section contains four conferences on texts from the Philokalia regarding vigilance.

Monasticism

The All-Embracing Gift of the Holy Spirit. An Approach to the Monastic Legacy of Saint Sophrony

In this review, I highlight two themes in the book which will resonate with those familiar with Benedictine monasticism: humility and obedience. According to St. Sophrony, human society is structured as a pyramid in which the base consists of the lowest class—the masses, the poor, and the downtrodden. At its peak are the leaders of nations who “exercise lordship and authority over them”2Ibid., p. 23.. In contrast to this, St. Sophrony describes an inverted pyramid of humility. In his incarnation, Jesus turned the pyramid of this world upside down and “placed Himself at its apex, bearing the entire weight of its injustice, taking upon his shoulders the sins and the curse of the whole world”3Ibid., p. 24.. While human persons seek to “ascend to a certain social, economic, or professional sphere; to rise to pre-eminence, mastery, and power . . . , the path of the Lord is a descent, even to the nether regions; it is kenosis, pain, suffering . . .”4Ibid., p. 24.. However, at the summit of the inverted pyramid one finds life and light. Although Christ lived our human tragedy, there was no tragedy in Him. He gave his peace to His disciples.

Monasticism is the closest imitation of this path of Christ—his kenotic descent and his glorious ascent to heaven. As Jesus descended to hell, “those who are drawn to follow Him strive to search out the entire length of His path, to know Him more deeply and love Him more ardently”5Ibid., p. 43.. For monks and nuns this involves not comfortable living and pleasure or preserving one’s own good name, but spiritual struggle, enduring injustice, and suffering while blessing the Lord. They “never cease going downwards, condemning themselves as unworthy of God”6Ibid., p. 44.. Archimandrite Zacharias tells his brother monks, “We deem ourselves worthy of this hell, yet we do not despair. There is acceptance with courage, total confidence in the mercy of God and in His providence for our life”7Ibid., p. 397..

Obedience is closely connected to this humility. When “taken seriously as the foundation of monastic life, it renders monasticism truly prophetic, so that it witnesses to the indescribable humility of Christ”8Ibid., p. 14.. One practices obedience to one’s elder (spiritual father), one’s hegumen, and to one’s brothers and sisters. Monasticism “constitutes the spiritual relationship of the disciple with his Elder, who takes upon himself the death of his disciple and imparts to him life. . . . As for the Elder, he is the one who loves his disciple with the ‘mad’ love of God, thirsting for his salvation, which is also his own salvation and glory”9Ibid., p. 71.. The Hegumen seeks to always remain in God’s will and prays that God will give him a word for the monks who come to him. Monks approach him with great reverence, seeking to “snatch his first word as God’s will”10Ibid., pp. 68-69.. Obedience is also shown by competing in honoring others more than oneself, supporting others in the tasks that they have been given, and by praying by name for all one’s brothers/sisters in community. Archimandrite Zacharias states:

If, however, each time we present ourselves before God, we pray by name for all our brethren without omitting even one, our monastic life will become a feast in our heart. Seeing the total number of the brethren in our heart at the time of prayer, the Lord is well pleased and will slowly enlarge our heart to embrace heaven and earth and make us partakers of His divine universality11Ibid., pp. 63-64..

When our “whole being expands in a universal enlargement, desiring that which is the very core of God’s holy will: that none should perish,” our prayer takes on cosmic dimensions and renders us as intercessors between God and humanity12Ibid., p. 61..

This brief exploration of the themes of obedience and humility in Monasticism: The All- Embracing Gift exemplifies how Archimandrite Zacharias, utilizing the tradition he inherited from Sts. Silouan and Sophrony, explicates how following Christ in daily monastic life is intended to lead us to a depth of prayer and breadth of charity that truly seeks the salvation of all. There are many more riches to be found in this book. It is a book to be recommended for slow, prayerful reading.

Footnotes

- 1Archimandrite Zacharias, Monasticism, p. 51.

- 2Ibid., p. 23.

- 3Ibid., p. 24.

- 4Ibid., p. 24.

- 5Ibid., p. 43.

- 6Ibid., p. 44.

- 7Ibid., p. 397.

- 8Ibid., p. 14.

- 9Ibid., p. 71.

- 10Ibid., pp. 68-69.

- 11Ibid., pp. 63-64.

- 12Ibid., p. 61.