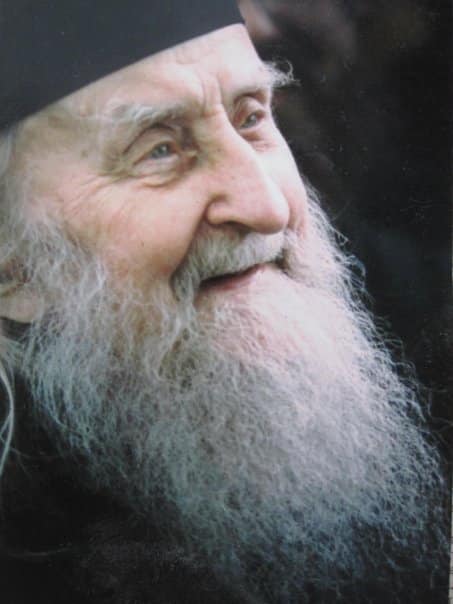

Elder Sophrony was born in Moscow on the 22nd of September 1896 and named Sergei Simeonovich Sakharov. Sergei Sakharov grew up in a large Orthodox family with four brothers and four sisters. As a young child, he assimilated the spirit of prayer from his nanny, who would take him with her to church and he would pray for up to three quarters of an hour at a time.1Cf. Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), Letters to His Family, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2015), p. 24. It was during his early years that he first encountered the Uncreated Light which would remain for ever imprinted in his memory.2See Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), We Shall See Him as He Is, trans. Rosemary Edmonds, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2004), p. 37.

At the end of his secondary school education, he enrolled in a private art foundation course. In 1918, he applied for entrance into the Moscow School of Fine Arts. At that time, the First World War had already broken out and, soon after, the Bolshevik Revolution started. However, Elder Sophrony was never sent to the front line. As he was already a student in the School of Fine Arts, he was assigned instead to the Department of Camouflage.3Ibid., pp. 23-24. This meant that he avoided direct combat and later on he was very grateful for this because there was no canonical impediment when he was asked to become a priest.

During the First World War and the civil strife within his own country, he was deeply affected by the catastrophic spectacle of human suffering. As he himself relates, one morning in a street in Moscow, an intractable thought came into his mind: ‘the Absolute cannot be “personal”, eternity cannot lie in the “psyche” of Gospel love…’4Ibid., p. 32. He withdrew from his childhood prayer and became alienated from the God of his Fathers.

Many artists at this time in Russia experimented with Eastern religions5Sister Gabriela, Seeking Perfection in the World of Art, The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2014), p. 63. and the young Sergei saw in them a logical solution to the grievous sight of suffering and pain. He practiced meditation of a non-Christian character for about eight years. Yet as his experiment with eastern religions was ‘out of ignorance’6Cf. 1 Tim. 1:13. God had mercy on him and led him back to the true worship of the Personal and Living God of Revelation.

In his letters, he says that at this time he felt that while he was walking on the earth and speaking to people, he did not feel the earth beneath his feet but an endlessly deep, black chasm.7See Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), Striving for Knowledge of God, trans. Sister Magdalen, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2016), p. 73. He was faced continually with the burning question which had haunted him since his early youth: ‘Am I eternal along with everyone else, or are we all destined for the black night of non-being?’ He was granted the grace of perceiving the dark veil of death and despair which envelop mankind and all life on earth.

After the Revolution, Sergei fled abroad. He passed through Italy and Berlin in Germany, and finally settled in Paris at the end of 1922. In the years of his sojourn in Paris, he exhibited works of art in 1923 at the Salon d’Automne and in 1924 at the Salon des Tuilleries.8See Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), Striving for Knowledge of God, trans. Sister Magdalen, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2016), p. 73.

It was in Paris that Sergei returned to the Church His conversion occurred when he came to know the true content of the revelation given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai, ‘I AM THAT I AM.’9Exod. 3:14. See also Archimandrite Zacharias (Zacharou), Christ, Our Way and Our Life, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2012), p. 11. By God’s grace he understood that the Absolute Being that he sought is none other than the personal God, Christ Himself. In 1924, on Holy Saturday, he experienced the Uncreated Light in such a way that he felt his personal resurrection and along with it the resurrection of the whole world. Saint Sophrony described this event in the third person in a letter:

I know a man in Paris who from Holy Saturday until the third day of Easter, throughout three days, was in a state of theosis, something he could only express, within our earthly reference, by saying that he ‘beheld the dawn of the day without eventide’. ‘The dawn’ because the light was unusually delicate, fine, ‘tender’, in some ways sky blue in colour. ‘The day without eventide’ is eternity.10Striving for Knowledge of God, p. 234.

After this vision of the light, Sergei ceased to exhibit paintings and distanced himself from his social circle. In April 1925, he began a course at the newly founded Saint Sergius Theological Institute, but before long he abandoned it and one day, returning from his lectures, he felt the desire to enter a monastery. Quite soon after this an opportunity suddenly occurred for him to travel to Greece and so he went to Mount Athos.11See ibid., p. 29.

During the autumn of 1925, Elder Sophrony arrived at the Holy Monastery of the Great Martyr Saint Panteleimon. He received the monastic habit on the 11th of March 1926 and on the 5th March of 1927 he was tonsured into the Small Schema. After five years, Father Sophrony became acquainted with Saint Silouan. From the first days of his coming to the monastery Father Sophrony had seen the Saint in passing and felt a great reverence towards him. Whenever they came across each other, Elder Sophrony observed that his face shone with an indescribable light and beauty. However, the first time they spoke was after Father Sophrony was ordained deacon on the 30th of April 1930 by Metropolitan Nikolai Velimirović of Žića and Ochrid.12Recently canonised by the Holy Synod of the Serbian Patriarchate. Saint Silouan was present at the ordination. Soon after the ceremony, Elder Sophrony received a new visitation of the Uncreated Light which lasted for two weeks.13See We Shall See Him as He Is, pp. 184-185. Not long after this, Saint Silouan came to hear of some advice Father Sophrony had given to one of their brothers at Saint Panteleimon, and recognising in it something of his own experience, he spoke to him about the matter concerned.

Saint Silouan recounted how after fifteen years of wrestling with demons, one evening thoughts of despair encircled him in such a threatening way that he turned to the Lord saying: ‘Lord, teach me what to do so that the demons no longer torment me.’ Then he heard the following response of the Lord in his heart: ‘Keep thy mind in hell and despair not.’ From that moment on, he was freed from inner struggle and deep peace reigned in his heart, as this word gave him the power to humble himself, lowering himself below every created thing.

Later Elder Sophrony would say that meeting Saint Silouan was the greatest gift of God in his life. Through the Saint’s revelatory word, he learned to preserve his mind free from every intrusive thought by means of the fire of charismatic self-accusation. During their first private meetings together, Saint Silouan entrusted to Father Sophrony a collection of his notes which were written in phonetic Russian. He asked Father Sophrony to edit and publish them.

In the first weeks of 1935, Father Sophrony became seriously ill with malaria and because he was thought to be close to death on the 18th of January he was tonsured to the Great Schema in the church of the sick bay, and, perhaps due to that, he recovered. Over the following years, his health continued to trouble him, and he would often retire during the day to a hermit’s hut near the monastery grounds. During this time, he also helped Saint Silouan in his correspondence and meetings with those who turned to him for advice. Towards the end of his life Saint Silouan advised Father Sophrony to ask for a blessing to leave the monastery and live as a hermit.

After Saint Silouan passed away on the 24th of September 1938, Elder Sophrony sought a blessing from the Abbot of the monastery, Missail, to withdraw to the awesome desert of Karoulia. He lived in the desert for the period which coincided with the Second World War. During this time, he wrestled with God, praying like a madman, as he once said, for peace in all the world.14See Striving for Knowledge of God, p. 258.

On the 2nd of February 1941, he was invited by the Holy Monastery of Saint Paul to be ordained to the priesthood so that he could serve as a spiritual father. The ordination was performed by Metropolitan Hierotheos of Melitoupolis, who had retired to Mount Athos. Over the following years, Elder Sophrony’s ministry included the Holy Monasteries of Simonopetra, Gregoriou and Xenophontos. He was also a spiritual father to many who were living in cells and to hermits. In February 1947, after twenty-two years on Mount Athos, he asked for a blessing to leave Mount Athos and stay in Paris for a year to edit and print the writings of Saint Silouan.

Despite his grave ill-health and extreme poverty, Elder Sophrony worked hard and within a year of his arrival in Paris, he had managed to produce a first edition of his book on Saint Silouan in Roneotype. In writing the biography of Saint Silouan, Elder Sophrony set out a pattern of writing the life of a saint which was truly original, as he focused on the inner life of his Elder and through this, he answered the burning questions of his generation.

Elder Sophrony exhausted his strength completing his biography of Saint Silouan which he self-published in Russian in 1948. The hardship of the preceding years and the privations he had suffered during the Second World War resulted in a serious stomach ulcer, and in the same year he was finally forced to undergo a nearly complete gastrectomy. In hospital, on a drip for eighty days, he only just managed to survive. He was transferred as an invalid to a Russian home for the elderly at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, on the outskirts of Paris. Whilst he was recuperating there, a variety of people started to come to him for spiritual guidance, both residents of the home and others.

As time went by, his younger disciples began to express with increasing persistence their desire for Elder Sophrony to establish a monastery so that they could live the monastic life near him. At first, he was hesitant because of his poor health. Eventually, however, he took pity on them and started looking for a suitable place. The site where he was to build his monastery in Essex, England was found with the help of English friends. In 1958, his book on Saint Silouan had been published in English, entitled The Undistorted Image, and the translator of the book, Rosemary Edmonds, was instrumental in finding a property for his small community. Through a series of unbelievably miraculous events, the providence of God enabled Elder Sophrony to obtain permission from the British Government to settle in England, and on the 5th of March 1959 he arrived in Tolleshunt Knights, Essex, with a small group of people ready to set up his community. At that time the place was virtually deserted and Elder Sophrony was glad because, as he said, no one would be interested in it and therefore he would not be depriving anyone of it.

Life in the monastery in the early years was very quiet. The small community was hidden and invisible, sustained by the wealth of Elder Sophrony’s word and the services in the chapel. As the congregation grew, the life of the monastery began to change and Elder Sophrony dedicated himself to the ministry of confession, receiving the faithful day and night. He was simple and natural with everyone, and honoured them all, making each one feel his own uniqueness on the earth and in the sight of God. He identified with everyone and did not favour anyone especially. Although his spirit was constantly taken up with prayer for the salvation of the whole world, his mind was never apart from his monastery and his word, loaded with grace, originated from another world.

During the first decades after the community had moved to England, the building and decorating of the churches of the monastery required much of his prayer and attention. After having abandoned painting for many years, he began to paint icons and frescos for the new places of worship. He strove to express the Face of Christ which had been revealed to him in the Light. However, he was never satisfied with his work and often adjusted and repainted the icons of Christ he had created.

Numerous miracles were witnessed during his life, on the day he died, and also after his death. Many were healed of incurable illnesses, the bonds of barren women were loosed, people suffering from psychological illnesses began to function normally again and, above all, many who had been broken by the sickness of sin were made whole. However, we have deliberately avoided emphasising the Elder’s miracles because he was above all a man of the word of God. Every encounter with him, even the most simple, was quite out of the ordinary. His slightest word had the power to inform the heart of whosoever drew near to him with grace. He prayed long and fervently for those who suffered, and if their hearts were transformed by his word or his prayer, he would rejoice more than if a visible miracle had taken place. We therefore feel that we too should emphasise this aspect after his death.

When Elder Sophrony felt that his end was drawing near, he said to one of the monks: ‘I have told God everything; now I must go.’ He then wrote a moving letter to the All-Holy Ecumenical Patriarch, humbly and wholeheartedly thanking him for the kindness he had shown the monastery and boldly entreating him to defend the helpless work of his hands:

Do thou in whose power it lieth to bless, bless the humble sheep of our fold, and leave not out of thy tender care and goodwill, this place, which, though small, poor and insignificant, hath been founded upon many tears, deep sighs, and with much blood and sweat.

Having commended the monastery to the protection of the Patriarch, he asked for his blessing to depart this life ‘unto the longed-for Light of Christ’s Resurrection’. In his last days he asked to see all the Fathers and brethren of the monastery individually and gave a final word to each. Having weakened, he had taken to his bed, whereas before he had always slept at intervals in an armchair. For the last four days of his life, he kept his eyes closed and would not speak. When we asked for his blessing he would simply raise his hand and bless us. He departed in prayer to the beloved God of his Fathers on Sunday, 11th of July 1993, at the age of ninety-seven years.

Footnotes

- Cf. Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), Letters to His Family, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2015), p. 24.

- See Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), We Shall See Him as He Is, trans. Rosemary Edmonds, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2004), p. 37.

- Ibid., pp. 23-24.

- Ibid., p. 32.

- Sister Gabriela, Seeking Perfection in the World of Art, The Artistic Path of Father Sophrony, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2014), p. 63.

- Cf. 1 Tim. 1:13.

- See Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), Striving for Knowledge of God, trans. Sister Magdalen, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2016), p. 73.

- See Letters to His Family, pp. 31-32.

- Exod. 3:14. See also Archimandrite Zacharias (Zacharou), Christ, Our Way and Our Life, (Tolleshunt Knights, Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist, 2012), p. 11.

- Striving for Knowledge of God, p. 232.

- See ibid., p. 29.

- Recently canonised by the Holy Synod of the Serbian Patriarchate.

- See We Shall See Him as He Is, pp. 184-185.

- See Striving for Knowledge of God, p. 258